Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Informational ground: background and foreground

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

46-3

26-4-2022

1562

Informational ground: background and foreground

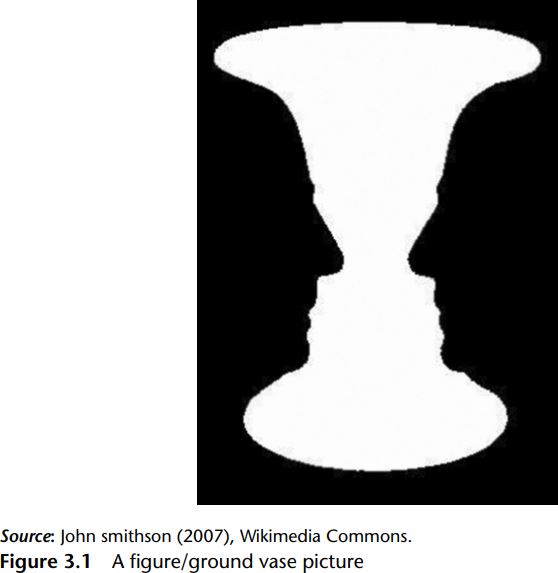

One general way of approaching the issue of background and foreground is to adopt a notion that arose out of the Gestalt psychology of the 1930s and 1940s, namely, the issue of figure and ground in visual perception. A picture will typically have foregrounded elements, the figure, and backgrounded elements, the ground. The perception of one is influenced by the other. In fact, what fascinated researchers such as Edgar Rubin, a Danish psychologist, were pictures whose figure and ground could be reversed and a new interpretation derived. This is illustrated by his famous vase picture published in Synsoplevede Figurer (Visually Experienced Figures) (1915), many variants of which have been produced.

In one interpretation, one sees a vase; in another interpretation, one sees two heads in profile. Moreover, in one interpretation the vase is the figure, but in the other it is the ground. This means that one cannot perceive the picture as a vase and two faces simultaneously. How might this work in language?

Some approaches (e.g. Chafe 1976) address the issue in terms of given information and new. These correspond to background and foreground respectively. In fact, we already met such issues, where the notion of givenness was aired in reference to Gundel et al.’s (1993) Givenness Hierarchy, a subtle view of the distinction between given and new information expressed in cognitive terms.

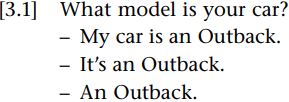

You may recollect that they propose a scale to do with whether referents are in the foreground or background in terms of the knowledge and attention state of the addressee. Thus, something which the discourse has brought into focus right now, something which is active in the mind, something which is in memory but is not currently active and something completely unknown would all have different cognitive statuses. Generally speaking, cognitive status concerns the extent to which something is cognitively foregrounded in the minds of participants. Consider this question and its possible answers:

The answers progressively pare down the information they express to the bare essentials, the new information that answers the question, namely, an Outback. In the first answer, my car is repeats material from the question, information that is already given in the discourse. It is thus not surprising that the second answer can use a pronominal form and the third can omit the given information altogether.

For reasons of economy, the third or the second answer sound much more like what one would actually get in naturally occurring conversation. Of course, there is no requirement of actually saying the item in the previous discourse for something to be taken as given. Consider these possible exchanges said at a car club meeting:

In example [3.1], the discourse of the question brought the notion of the car into focus. In [3.2], the question does not bring the car into focus, but it is said in a context in which it can be readily assumed that all participants have cars. This assumption is given information. Hence, again, only an Outback supplies new information and the third answer takes full advantage of possible economies (arguably, one could also ditch the indefinite article).

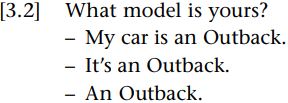

In fact, the third answers in [3.1] and [3.2] are in tune with the discourse of example [3.3] (punctuation as per original; we have numbered the turns for ease of reference). Here, a member of a car bulletin board reconstructs a conversation he had at a car scrapyard, where he was searching for a particular part.

Turns (5)–(6) support the point we were making above: there is no need for the answer in (6) to include “model”, as that is discourse-old (cf. any model). Moreover, there is no need for the question to specify “what model of car”, because in that context it can readily be assumed that “model” pertains to cars. So why does the scrap dealer say: what model is your car (line 7). This relates to the kind of interactional issues. Throughout this discourse it seems that each participant has different knowledge in mind, including different understandings of common knowledge. The scrap dealer “knows” that the customer is looking for a specific part for a specific model of a specific car and, further, that that part is for the car that the customer owns, which is why he tries to flush out the model of his car at the end. The customer, on the other hand, “knows” that the scrap dealer will not know much about the parts mentioned in (line 4) and hence, in (line 2), merely supplies the car year and make, knowing that all models of that make and year have the relevant part. Overall, then, each participant has a different conception concerning what is given. Each vies for power: the power of the expert, the one who “knows”. This conversation was posted on the car bulletin board in order to illustrate the stupidity of car scrap dealers and why it is not worth trying to get parts from them.

There is an alternative perspective on the background/foreground distinction. Some grammarians, realizing that sentence structure reflects the way people communicate information, adopted semantic notions that echo this distinction. It seems that the Prague School linguists of the early- to mid-20th century were amongst the first to propose a two-part structure in which the parts are connected by their “aboutness” relation (Fried 2009: 291). Topic (sometimes called theme or ground) refers to what is being talked about in the sentence, while focus (sometimes called comment or rheme) refers to what is being said about the sentence topic. The precise terms used and how they are defined is variable. Structural features are an important part of the definitions in work on grammar, for example by Chomsky (1965) and Halliday (e.g. 1994), and are briefly alluded to in work positioned on the interface between grammar and pragmatics (e.g. Lambrecht 1994). Regarding the topic, structural characteristics in English include: the nominal part of a clause; the constituent in the leftmost position (or occasionally the rightmost position); the subject; the thing which the proposition expressed by the sentence is about; and also the constituent lacking the focal accent. The focus, as one can guess, involves the aspects not covered by the topic (e.g. the verbal part plus its complement, the body of the clause, the predicate). Let us revisit part of [3.2] above:

My car is indeed a nominal part of the sentence, in leftmost position and the subject. In contrast, is an Outback is indeed the verbal part of the clause plus its complement, the predicate. Note a further characteristic of such structures: the definite noun phrase my car presupposes information assumed to be known (namely, that a car of mine exists), whereas the remainder of the sentence asserts the new information about the car. This represents yet another way of conceiving of the background/foreground distinction. We will be looking closely at presuppositions.

There is overlap between cognitive givenness/newness, concerning the status of information in the mind (e.g. whether it is old/new, the focus of attention etc.), and semantic givenness/newness, concerning the presentation of information in the sentence, especially how one part is about another part. This is not surprising, it facilitates the target’s processing if one starts with a topic containing easy to access, old information, which can then act as a background context for the focus containing the new information. Also, it comes as no surprise to observe that there is a connection between definiteness and topic. Recollect that, we defined definite expressions as items primarily used to invite the participant(s) to identify a particular referent from a specific context, which is assumed to be shared by the interlocutors. That “assumed to be shared information” is the subset of given information relating to common ground. However, there are occasions where there is little or no overlap between cognitive and semantic givenness. We will consider some of these Before leaving the notion of semantic givenness, we should emphasize that the term “topic” here should not be confused with discourse topic. The key difference is that discourse topic pertains to what a discourse is about, and a discourse could contain one or more sentences, whereas semantic topic generally pertains to a portion of information within a sentence. In the previous examples the discourse was clearly about cars and knowing this assisted in the selection of referents. There are occasional exceptions where a whole sentence can be construed as both a semantic topic and a discourse topic, but this is relatively rare. We will return to the notion of discourse topic, specifically when we discuss context models.

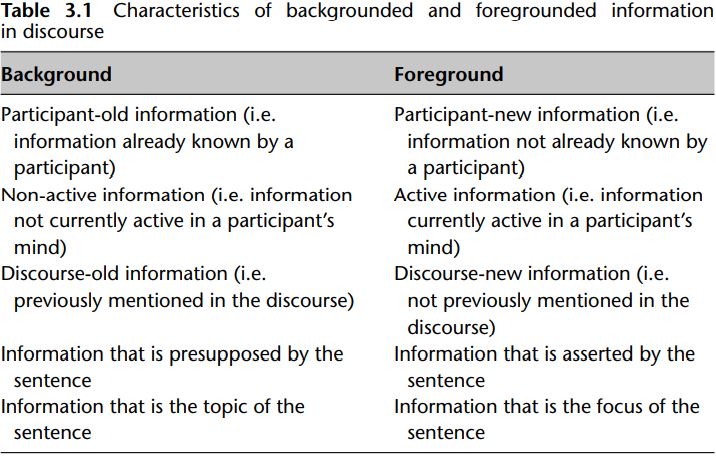

Let us take stock. Some of the relevant characteristics of backgrounded and foregrounded information, broadly arranged from the more cognitive to the more linguistic, are captured in Table 3.1.

We have already touched on matters relating to the first three characteristics, where we discussed some cognitive aspects of understanding referring expressions. We will periodically connect with and elaborate the characteristics of Table 3.1.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)