Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Referring expressions in interaction

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

41-2

26-4-2022

943

Referring expressions in interaction

We have raised a number of issues that are key to interaction, including the idea that (1) referring expressions are not simply enriched by context but can also help construct it; (2) the choice of referring expression is influenced by the speaker’s assumptions about the degree to which the referent is in the target’s mind (i.e. its cognitive status) (see also Isaacs and Clark 1987, for experimental evidence); and (3) the choice of referring expression is influenced by assumptions about the common ground that pertains between specific interlocutors (see also Brennan and Clark 1996, for experimental evidence). All these go beyond our initial idea of inviting a participant to pick some particular referent out of a specific context. This section briefly explores two further notions at the heart of interaction. One is that the process of choosing and enriching referring expressions is dynamic (it is worked out in the course of interaction), and the other is that that process is emergent (it is not predetermined by certain combinations of referring expression and context).

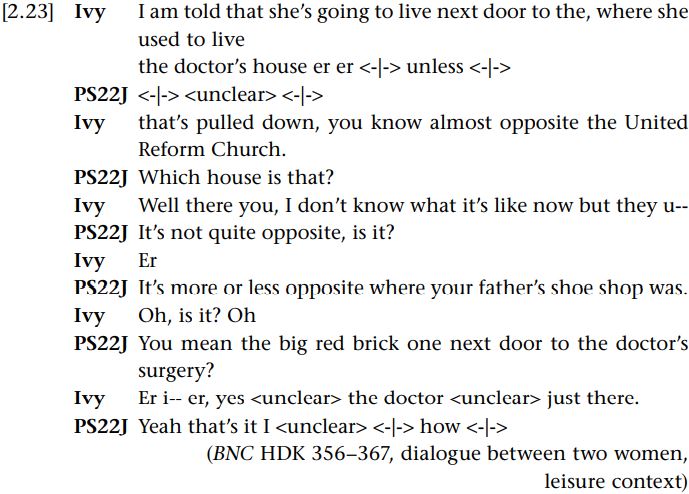

As we noted, shared discourse plays a role in feeding common ground. Here we see the participants using discourse to establish common ground. Example [2.23] illustrates how what is being referred to, the referent, emerges in the interaction, and how the two interlocutors collaborate in working it out.

Clearly, Ivy wants to specify where the referent of she is going to live, but is having difficulty. Note the incomplete definite noun phrase “next door to the”. Together they work it out through spatial deixis (next door twice, opposite three times), mapping out the location through questions and answers. The eureka moment comes with PS22J’s hugely descriptive definite noun phrase the big red brick one next door to the doctor’s surgery, assisting Ivy in identifying the location. And when Ivy confirms the referent of this noun phrase, PS22J switches to anaphoric it.

A key scholar to have explored conversational interaction and referring expressions, specifically anaphora, is Barbara Fox (1987, 1996). Fox (1987: 16) argues that there is a continuous interaction amongst the following three steps of reasoning:

1. Anaphoric form X is the “unmarked” form for a context like the one the participant is in now.

2. By using anaphoric form X, then, the participant displays a belief that the context is of a particular sort.

3. If the participant displays the belief that the context is of a particular sort, then the other parties may change their beliefs about the nature of the context to be in accord with the belief displayed.

Just as we have been discussing above, for Fox (1987: 17) “anaphoric choice at once is determined by and itself determines the structure of the talk”. Also note that “change” is built in, as beliefs about context change then what counts as unmarked changes for the selection of the next form. What this means, then, is that the usage of referring expressions and what counts as their referents in context is not only a two-way street but a street whose direction is constantly shifting as it is mapped out by its traffic, or, to put it another way, the meanings of referring expressions emerge in a dynamic fashion as the interaction progresses.

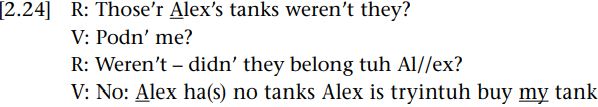

Fox (1987: 18–19) suggests that the basic pattern in non-story conversation is that first mentions of a referent in a sequence are done with a full noun phrase, and thereafter a pronoun is used to display an understanding that the sequence is not closed (conversely, using a full noun phrase displays an understanding that it is closed). However, what counts as a sequence varies from genre to genre. As we have seen in the reflection box on variation across English written registers, the usage of referring expressions varies hugely across genres, so what will count as unmarked will vary. Moreover, note that this is a “basic” pattern; participants can exploit it. One context in which this can happen is disagreement. Note the final line of this example from Fox’s data (Fox 1987: 62):

Here, the use of a proper noun Alex instead of the pronominal he is geared towards attracting the attention of the first speaker to the fact that her or his assumptions about Alex are incorrect. Moreover, Downing (1996: 136) observes that proper nouns can be usefully deployed in contexts “where the speaker wishes to display his or her authority to speak about a particular referent, as is common in disagreement contexts”, and this fits here.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)