Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Using and understanding referring expressions in interaction

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

33-2

26-4-2022

735

Using and understanding referring expressions in interaction

Referring expressions and context

The following is the beginning of Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest ([1962] 2003: 1):

This is a creative way to begin a novel; it creates psychological prominence. We have the outline of a puzzle here, but not the pieces with which to complete it. We know that some group of people (they) are located in some space away from where the speaker/writer is (out there). The referring expressions begin to build the point of view of one particular character, the protagonist, who is incarcerated in a mental institution. It flags the kind of context that needs fleshing out. This helps achieve the dramatic purpose of the novelist.

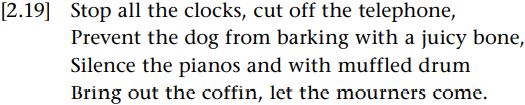

Let us look at another literary example. This is the first stanza of W.H. Auden’s poem Funeral Blues (Stop all the Clocks) ([1936]1976):

As we pointed out, definite noun phrases presuppose the existence of their referents, and can be used to invite the participant(s) to identify a particular referent from a specific context which is assumed to be shared. Thus, the definite noun phrase in The book you’re reading is great (example [2.3 (a)]) may be taken as identifying the book the speaker sees you reading, rather than, say, the one you read when you go to bed, because you both share (e.g. through physical co-presence, visual contact) that specific context. However, the definite noun phrases in the Auden poem are not like this. They presuppose the existence of clocks, telephone, dog, pianos, coffin and mourners, but in doing this they also construct the context in which the particular referents can be identified. They do not passively rely on a specific shared context for interpretation; rather, they construct a specific shared context in which they can be interpreted. These items construct a particular fictional world. More particularly, the items coffin and mourners in the final line trigger the contextual frame or schema of a funeral by virtue of the fact that they are stereotypical components of that contextual frame. Thus, they suggest the frame in which they can be identified as particular components, as opposed to simply being identified as particular components within a given frame.

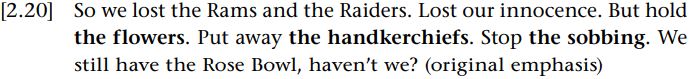

It is not surprising that literary-linguistic scholars have focused on how referring expressions in literature contribute to the creation of fictional worlds (e.g. Semino 1997). In fact, it is normal in all kinds of interaction for people to rely on information from context to interpret referring expressions and also to use referring expressions to help construct the contexts in which they are interpreted. It is a two-way street. Note that this is a radical departure from the traditional approach to referring expressions, which focuses on the context fleshing out the referring expression and not the referring expression signaling the context of which it is a part. An excellent example of the latter, cited by Epstein (1999: 58), appears in a newspaper. In this example, a sports commentary writer reflects on the city of Los Angeles’s loss of two professional football teams who used to play there:

Like the poem above (and probably partly inspired by it), the definite noun phrases the flowers, the handkerchiefs and the sobbing refer to stereotypical components of the frame of the funeral. The funeral frame itself is not mentioned prior to the usage of these definite noun phrases. As Epstein (1999: 58) comments, “the frame itself need not be directly evoked at all ... but can be activated simply by mentioning some of its salient elements”.

We wrote that “definite expressions are primarily used to invite the participant(s) to identify a particular referent from a specific context which is assumed to be shared by the interlocutors”. The use of “primarily” was judicious because the uses of referring expressions discussed– creating psychological prominence, expressing viewpoint or triggering frames – do not fi t well the idea of identifying particular referents from items in a given category. Epstein (1999) suggests that thinking in terms of “accessibility” is preferable, and we will expand on this notion.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)