Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

A first outline of pragmatics

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

7-1

9-2-2022

963

A first outline of pragmatics

A crucial basis for making pragmatic inferences is the contrast between what might have been uttered and what actually was uttered. Example (1.4) was a short, headed section from an information flyer about a restaurant. (Double quotes have been omitted because they would spoil the appearance, but this counts as a sequence of utterances. Remember that I am allowing utterances to be in speech, writing or print.)

The leaflet then switches to another topic, inviting us to infer that no provision is made for smoking. We cannot be certain. They might simply have forgotten to add something permissive that they intended to say about smoking, but it could be a pointedly negative hint to smokers. Nothing in the leaflet actually says that smoking is unwelcome or disallowed; so this implicature from (1.4) and its context is an elaboration well beyond the literal meaning of what appears in the leaflet.

Explicature, the second of the stages of interpretation described in Section 1.1.2, would have included working out that the heading in (1.4) is about coffee drinks, not, for instance, milkshake drinks .

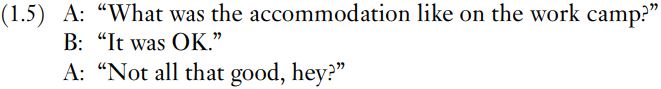

Example (1.5) shows a kind of pragmatic inference generally available when words can be ordered on a semantic scale, for instance the value judgements excellent > good > OK.

Speaker A draws an implicature from B’s response because, if the accommodation was better than merely OK, B could have used the word good; if it was very good B could have used the word excellent. Because B did not say good or excellent, A infers that the accommodation was no better than satisfactory. At the time of utterance, A might well have heard and seen indications to confirm this implicature – perhaps B speaking with an unenthusiastic tone of voice or unconsciously hunching in recollection of an uncomfortable bed. Such things are also contextual evidence for working out implicatures.

The stage of explicature – before implicature (see Section 1.1.2) – would have involved understanding that, in the context of A’s question, B’s utterance in (1.5) has as its explicature ‘The work camp accommodation was OK’, the work camp being one that B had knowledge of and which must previously have been identified between A and B, probably earlier in the conversation.

The pragmatic inferences called implicatures and explicatures occur all the time in communication, but they are merely informed guesses. It is one of their defining features that they can be cancelled. In (1.5), B could have come back with “No, you’ve got me wrong; the accommodation was good”. This would cancel the implicature, but without contradiction, because accommodation that is ‘good’ is ‘OK’, so it is not a lie to say of good accommodation that it was OK.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)