Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The English Perfect

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

149-13

7-2-2022

1739

The English Perfect

Another syntactic construction central to the tense–aspect system of English is the Perfect, exemplified in (17).

Analysts have found it difficult to classify the Perfect as an aspect or a tense. It has two constituents, has or have and a past participle, here blocked. (The label ‘participle’ is not helpful; it derives from the Latin words meaning ‘take part’ or ‘participate’ and is supposed to reflect the fact that in, for example, the Perfect construction, words such as blocked participate in two word classes. Blocked is related to the verb block but is itself a sort of adjective – compare The blocked track.) The participle indicates an action that is completed, and this is why the Perfect looks like an aspect; but has signals present time, and this makes the Perfect look like a tense. On the assumption that some constructions may simply be indeterminate, we make no attempt here to solve the problem.

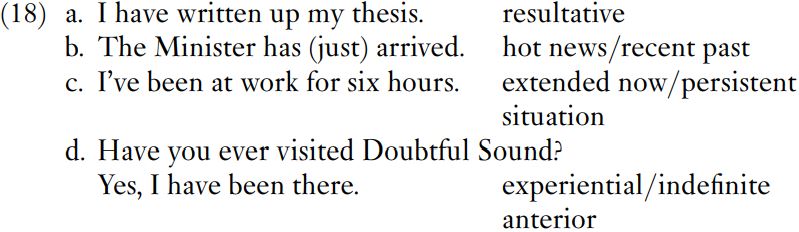

The Perfect has been defined as focusing upon the presently accessible consequences of a past event, rather than upon the past event per se; this is summed up in the traditional formula that the Perfect has current relevance. The Perfect in standard written English has four major uses, exemplified in (18).

Examples (18a–d) go from the most accessible to the least accessible consequences. The speaker who utters (18a) has the finished thesis to show (on disk or in paper form). If (18b) is uttered, the listeners know that the Minister is there with them. The speaker who utters (18c) is saying ‘I started work six hours ago and as you can see I am still here, mission unaccomplished’. The consequences of these three examples are visible, as are the consequences of (17), another resultative.

The consequences of (18d) are not so obvious. The question is about a possible visit at an unspecified time in the past, hence the term ‘indefinite anterior’. The answer, Yes, I have been there, does not specify a time but merely contains an assertion that a visit to Doubtful Sound took place. The consequences might be that the speaker can provide information about how to get to Doubtful Sound, or has happy memories of the landscape and sea, or still has lumps from the bites of the amazingly vicious sandflies.

The English Perfect has been the subject of much debate and analysis, and we can do no more than indicate the main points. We close this section with comments on three aspects of the English Perfect that are in need of investigation. Insufficient attention has been given to the role of just, in (18b), and of ever, in (18d), as demarcating the hot-news Perfect and the experiential Perfect from the other interpretations. Should (18b) and (18d) be treated as separate constructions, not just separate interpretations?

In written English the Perfect excludes definite time adverbs – *The snow has blocked the track last Monday evening. This appears to be because the Perfect focuses on the current, accessible consequences of an action, and speakers using the Perfect are not concerned with the action and time of action in the past. In spoken English, particularly spontaneous spoken English, this exclusion of definite past-time adverbs is beginning to break down.

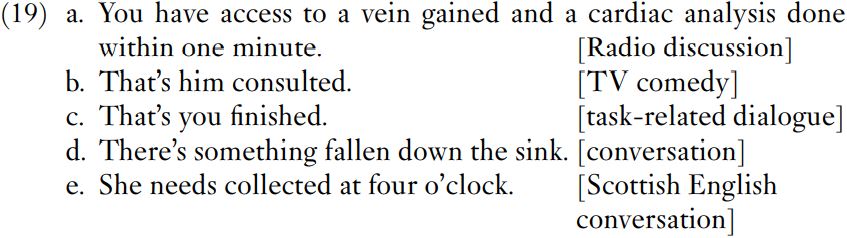

Finally, we should note that past participles were originally resultative, that is, they expressed the result of a completed action. The participles survive in a number of resultative constructions, not just in the resultative Perfect. Examples are given in (19). They are all examples taken from spontaneous speech.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)