النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

Splicing Can Be Regulated by Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancers and Silencers

المؤلف:

JOCELYN E. KREBS, ELLIOTT S. GOLDSTEIN and STEPHEN T. KILPATRICK

المصدر:

LEWIN’S GENES XII

الجزء والصفحة:

16-5-2021

2538

Splicing Can Be Regulated by Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancers and Silencers

KEY CONCEPTS

- Alternative splicing is often associated with weak splice sites.

- Sequences surrounding alternative exons are often more evolutionarily conserved than sequences flanking constitutive exons.

- Specific exonic and intronic sequences can enhance or suppress splice-site selection.

- The effect of splicing enhancers and silencers is mediated by sequence-specific RNA binding proteins, many of which may be developmentally regulated and/or expressed in a tissue-specific manner.

- The rate of transcription can directly affect the outcome of alternative splicing.

Alternative splicing is generally associated with weak splice sites, meaning that the splicing signals located at both ends of introns diverge from the consensus splicing signals. This allows these weak splicing signals to be modulated by various trans-acting factors generally known as alternative splicing regulators.

However, contrary to common assumptions, these weak splice sites are generally more conserved across mammalian genomes than are constitutive splice sites. This observation is evidence against the notion that alternative splicing might result from splicing mistakes by the splicing machinery and favors the possibility that many alternative splicing events might be evolutionarily conserved to preserve the regulation of gene expression at the level of RNA processing.

The regulation of alternative splicing is a complex process, involving a large number of RNA-binding trans-acting splicing regulators. As illustrated in FIGURE 1, these RNA-binding proteins may recognize RNA elements in exons and introns near the alternative splice site and exert positive and negative influence on the selection of the alternative splice site. Those that bind to exons to enhance the selection are positive splicing regulators and the corresponding cis-acting elements are referred to as exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs). SR proteins are among the best characterized ESEbinding regulators. In contrast, some RNA-binding proteins, such as

hnRNP A and B, bind to exonic sequences to suppress splice site selection; the corresponding cis-acting elements are thus known as exonic splicing silencers (ESSs). Similarly, many RNA-binding proteins affect splice-site selection through intronic sequences. The corresponding positive and negative cis-acting elements in introns thus are called intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs) or intronic splicing silencers (ISSs).

FIGURE 1 Exonic and intronic sequences can modulate splicesite selection by functioning as splicing enhancers or silencers. In general, SR proteins bind to exonic splicing enhancers and the hnRNP proteins (e.g., the A and B families of RNA-binding proteins [RBPs]) bind to exonic silencers. Other RBPs can function as splicing regulators by binding to intronic splicing enhancers or silencers.

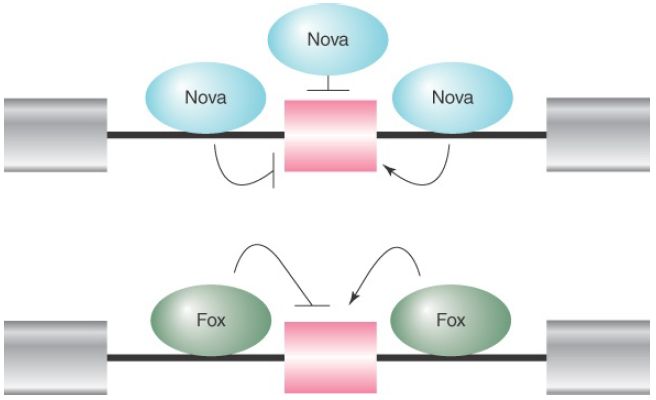

Adding to this complexity are the positional effects of many splicing regulators. The best-known examples are the Nova and Fox families of RNA-binding splicing regulators, which can enhance or suppress splice-site selection, depending on where they bind relative to the alternative exon. For example, as illustrated in FIGURE 2, binding of both Nova and Fox to intronic sequences upstream of the alternative exon generally results in the suppression of the exon, whereas their binding to intronic sequences downstream of the alternative splicing exon frequently enhances the selection of the exon. Both Nova and Fox are differentially expressed in different tissues, particularly in the brain. Thus, tissue-specific regulation of alternative splicing can be achieved by tissue-specific expression of trans-acting splicing regulators.

FIGURE 2 The Nova and Fox families of RNA-binding proteins can promote or suppress splice site selection in a contextdependent fashion. Binding of Nova to exons and flanking upstream introns inhibits the inclusion of the alternative exon, whereas Nova binding to the downstream flanking intronic sequences promotes the inclusion of the alternative exon. Fox binding to the upstream intronic sequence inhibits the inclusion of the alternative exon, whereas binding of Fox to the downstream intronic sequence promotes the inclusion of the alternative exon.

How a specific alternative splicing event is regulated by various positive and negative splicing regulators is not completely understood. In principle, these splicing regulators function to enhance or suppress the recognition of specific splicing signals by some of the core components of the splicing machinery. The bestunderstood cases are SR proteins and hnRNA A/B proteins for their positive and negative roles in enhancing or suppressing splicesite recognition, respectively. Binding of SR proteins to ESEs promotes or stabilizes U1 binding to the 5′ splice site and U2AF binding to the 3′ splice site. Thus, spliceosome assembly becomes more efficient in the presence of SR proteins. This role of SR proteins applies to both constitutive and alternative splicing, making SR proteins both essential splicing factors and alternative splicing regulators. In contrast, hnRNP A/B proteins seem to bind to RNA and compete with the binding by SR proteins and other core spliceosome components in the recognition of functional splicing signals.

SR proteins are able to commit a pre-mRNA to the splicing pathway, whereas hnRNP proteins antagonize this process. Given that hnRNP proteins are highly abundant in the nucleus, how do SR proteins effectively compete with hnRNPs to facilitate splicing?

Apparently, this is accomplished by the cotranscriptional splicing mechanism inside the nucleus of the cell . It is thus conceivable that the transcription process can affect alternative splicing. In fact, this has been shown to be the case. Alternative splicing appears to be affected by specific promoters used to drive gene expression, as well as by the rate of transcription during the elongation phase.

Different promoters may attract different sets of transcription factors, which may, in turn, affect transcriptional elongation. Thus, the same mechanism may underlie the influence of promoter usage and transcriptional elongation rate on alternative splicing. The current evidence suggests a kinetic model where a slow transcriptional elongation rate would afford a weak splice site emerging from the elongating Pol II complex sufficient time to pair with the upstream splice site before the appearance of the downstream competing splice site. This model stresses a functional consequence of the coupling between transcription and RNA splicing in the nucleus.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)