تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Siphoning Liquid Helium

المؤلف:

Franklin Potter and Christopher Jargodzki

المصدر:

Mad about Modern Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

p 72

25-10-2016

749

Siphoning Liquid Helium

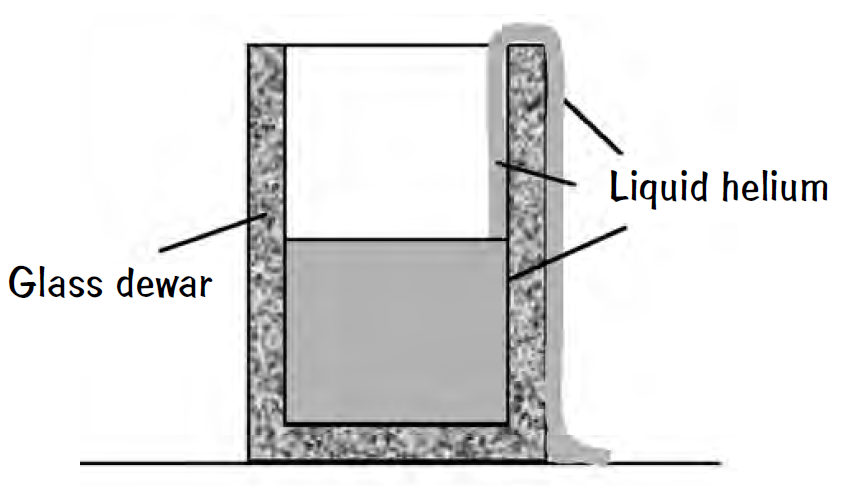

Liquid helium can crawl up the wall of its container without any additional help. How is this feat accomplished?

Answer

At temperatures near absolute zero, normal liquid He I becomes superfluid liquid He II by undergoing a secondorder phase transition. It's He atoms can move without viscosity in the superfluid. Superfluidity is a quantum mechanical phenomenon, with a macroscopic volume (centimeter dimensions) of liquid acting like a single macroscopic particle and described by a single-particle Schrodinger equation.

Immediately, superfluid He II in an open beaker will form a film that crawls up the walls, over the top, and down the sides until the beaker is emptied. Normal fluids also can be siphoned out of containers, but only if their motion is started externally! The solid surfaces in contact with He II are covered with a film 50 to 100 atoms thick along which frictionless flow of the liquid occurs. Supposedly, mass transport flow in the He II film takes place at a constant rate that depends only on temperature.

As the atoms of liquid He II move up the wall, they gain potential energy. What process provides the energy?

The answer lies in the ability of helium atoms to wet any surface that is, normal liquid He I atoms cling to the wall. The helium-helium force is the weakest force in nature because the K shell of electrons is complete and the helium zero-point motion is significant, so the helium-anything force is stronger. Hence helium atoms would rather be next to anything other than another helium atom. So He atoms quickly form a film when presented with the wall of the container because the helium–anything attraction lowers the potential energy and so on, while they gain gravitational potential energy. These He atoms clinging to the wall are no longer in the superfluid phase because their flow velocities are now lower than a critical velocity value.

The thickness of the film is usually limited to a few hundred atomic diameters because at some thickness the advantage of being near to the wall is canceled by the increase in gravitational potential energy. Then, while the normal fluid is clamped to the wall, the superfluid He II flows freely as the He atoms on the wall act as a siphon.

الاكثر قراءة في طرائف الفيزياء

الاكثر قراءة في طرائف الفيزياء

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)