تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Ferromagnetism

المؤلف:

Franklin Potter and Christopher Jargodzki

المصدر:

Mad about Modern Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

p 54

18-10-2016

705

Ferromagnetism

Why are so few substances ferromagnetic, yet practically all materials exhibit paramagnetic behavior?

Answer

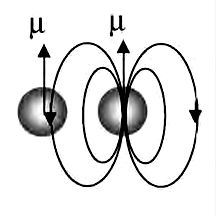

Many atoms and molecules have an inherent magnetic dipole moment. When we assume that each dipole behaves independently of its neighbors except for its alignment, the magnetic field direction next to the dipole is opposite to the direction in which the dipole itself points. In paramagnetic substances the dipoles are far enough apart to behave approximately independently, and when no applied field is present, these dipoles have random orientations. Each dipole is affected by the applied magnetic field but not by its neighbors. The applied magnetic field competes with the random thermal motion to cause a net magnetization that increases nearly linearly with the strength of the applied field, the ratio being known as the magnetic susceptibility.

When the density of magnetic dipoles becomes high enough for neighbors to affect each other, only neighbors in the head-to-tail configuration will tend to align one another. The side-by-side neighbors will be oppositely aligned because all the fields from its neighbors are opposite at its location. Thus every other dipole in each layer of the crystal will be aligned and form one sub lattice, like the white squares on a checkerboard, and the remaining dipoles (on the black squares) will form a second sub lattice of dipoles pointing in the opposite direction. The two sublattices interact strongly or ferromagnettically, but they cancel each other’s magnetization. Therefore, when magnetic dipole moments are crowded together, they are more likely to disalign their nearest neighbors than to align them. So ferromagnetism is rare.

Then how can ferromagnetic substances exist at all? Via a cooperative effect when the dipoles are very close and no longer behave independently. In these conditions a state of lower energy can form if groups of dipoles align each other into magnetic domains that themselves point in random directions. With an applied field, these domains will change their sizes to find the lowest energy state. Of course, domain formation cannot form above a certain temperature called the Curie temperature, because the thermal agitation interferes with the dipole interactions. Above the Curie temperature the substance becomes paramagnetic.

الاكثر قراءة في طرائف الفيزياء

الاكثر قراءة في طرائف الفيزياء

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)