Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Structural restrictions: General mechanisms

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P45-C3

2025-01-08

117

Structural restrictions: General mechanisms

As pointed out by Rainer (1993:98), the search for general restrictions is basically a characteristic of generative approaches to morphology, which is a comparatively young discipline. Perhaps due to this fact, many of the hypotheses are doubtful or outright untenable.

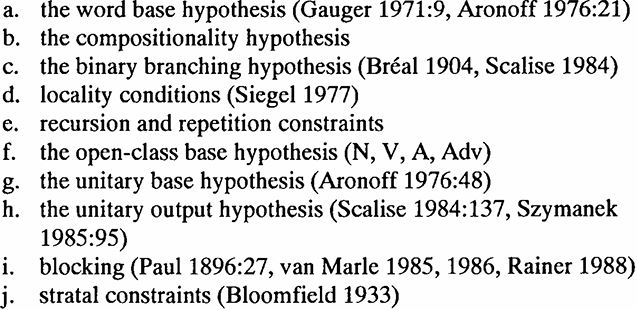

In (1) I have compiled the most important general restrictions as they can be found in the pertinent literature. Where appropriate, major proponents of the restrictions are named:

(1)

My comments on the restrictions listed in (1a-1f) will be kept to a minimum, because they are only of secondary relevance for the investigations to follow. A more thorough discussion will be devoted to points (1g-1j), since the morphological processes investigated can be seen as test cases for these restrictions.1 For a more comprehensive discussion of the hypotheses (1a-1f) the reader is referred to Rainer's (1993:98-117) excellent survey of general restrictions on word-formation.

The word base hypothesis claims that "all regular word-formation is word-based. A new word is formed by applying a regular rule to a single, already existing word" (Aronoff 1976:21). As pointed out by Aronoff (1976:xi), the term 'word' is to be understood in the sense of 'lexeme', not in the sense of inflected word (see also Aronoff 1994). This position is obviously designed as an alternative to morpheme-based approaches to the structure of words. Later authors have argued that Aronoffs first formulation of the word base hypothesis is too strong because it restricts the application of rules to already existing words. As mentioned by Booij (1977:21-22) and many others, possible words may also serve as bases for derivation or compounding. Taking this objection into account, the hypothesis still makes two predictions, namely that the bases of word-formation are neither smaller nor larger than the word. For the majority of processes this prediction is certainly correct, but many apparent or real counterexamples have been pointed out in the literature. This leads Dressier (1988) to the position that the generalization expressed by the word base hypothesis is a statistical rather than a strict universal, and one which should be explained by a theory of preferences as provided by Natural Morphology.

The compositionality hypothesis states that the meaning of a form derived by a productive rule is a function of the meaning of the rule and the base. This is fairly uncontroversial, although some attempts have been made to argue for a holistic interpretation of derived words, most notably by Plank (1981). However, only clearly analogical formations such as German Hausfrau - Hausmann 'housewife (female - male)' constitute unequivocal cases of holistic interpretation, while with truly productive rules the difference between holistic and compositional interpretations is empirically impossible to pin down.

The binary branching hypothesis seems to be untenable with all structures that are semantically coordinate and involve more than two elements. Dvandva compounds as in a German-French-English corporation or a phonological-semantic-syntactic approach are therefore systematic counterexamples, which indicate that the standard binary branching of non-coordinative structures is best viewed as a consequence of their semantics.

Following syntactic locality constraints like Chomsky's adjacency condition (1973) several locality restrictions on the structure of words have been proposed, such as Siegel's (1977) and Allen's (1979) 'adjacency principle', E. Williams' (1981) 'atom condition', or Kiparsky's (1982a) 'Bracket Erasure Convention' . As shown by Rainer (1993:105-106), the theoretical value and the empirical adequacy of these conditions is questionable.

It has often been noted that, unlike syntactic and compounding structures, derivational structures are not recursive (e.g. Stein 1977:226), or that affixes (e.g. Uhlenbeck 1962:428) or suffixes (Mayerthaler 1977:61, Corbin 1987:596-501) may not be iterated. Chapin (1970) has pointed out that examples like organizationalization demonstrate the possibility of recursion even in derivational morphology, though subject to general processing constraints. The iteration of prefixes is certainly possible in English (cf. anti-anti-abortion) and the impossibility of iteration of suffixes (*readableable, *conceptualal) follows from independently needed properties or constraints, for example of a semantic nature. It could also be argued that the non-iteration of morphological material is caused by (morpho-)phonological mechanisms, i.e. haplology (e.g. Plag 1998).

Another, oft-cited universal constraint on word formation concerns the classes of possible base words. Aronoff (1976:19, 21) states, for example, that both base and derivative must be members of the open class categories noun, verb, adjective and adverb. Although the constraint makes correct predictions (counterexamples are rare, but include, for example phrasal categories2), it remains to be shown whether we are really dealing with a formal constraint or whether the constraint follows from independent functional principles (see the discussion in Rainer 1993:109-110).

We may now turn to the restrictions that are more relevant for the investigations to follow, namely the unitary base hypothesis, the unitary output hypothesis, blocking, and stratal constraints.

1 For example, my analysis of derived verbs casts serious doubts on the unitary base hypothesis (UBH) and certain kinds of blocking, but supports the unitary output hypothesis (UOH).

2 Baayen and Renouf (1996) list the following attested examples involving -ness: next-to-nothing-ness, thatitness, over-the-topness, olde-worlde-ness.