Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

REFLECTING THE PYRAMID IN PROSE

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

203-12

2024-10-02

296

You will recall I said at the very beginning that writing anything clearly consists of two steps: first decide the point you want to make, then put it into words. Once you have worked out your pyramid structure and rechecked the thinking in your groupings, you know exactly the points you want to make. You also know the order in which you want to make them. All that remains is for you to put them into words.

In theory this should be a relatively easy task. One ought to be able to expect the normal business writer to translate his pyramided points into a series of concise, graceful sentences and paragraphs that clearly convey a lively message and capture the reader's interest. Alas, it does not always happen. The average sentence, far front being concise and graceful, is long-winded and heavy with jargon. This makes the paragraphs seem impenetrable and the subject endlessly boring. Let me give you a sampling:

- A primary area of potential improvement is improving cost-effectiveness of field sales-force deployment (and organization) to reflect the need for redefined selling missions at store and indirect levels dictated by changes in the trade environment.

- Preplanned adjustments may be developed from the alternative preliminary plans submitted by the Group and be in the form of outlines of contingency plans and prioritized guides to adjustments in special programs and other discretionary expenditures.

- Current needs for accurate cash flow analyses are particularly demanding upon the existing system; it is not prepared to meet the stringent accuracy requirements. Improvements are available through incorporating information not adequately considered in making projections.

These passages were produced by bright, articulate people with excellent problem solving skills. Any one of them can explain his ideas orally and be completely comprehensible. But they appear to believe that, in writing, the more dehydrated the style and the more technical the jargon, the more respect it will command.

This is nonsense. Good ideas ought not to be dressed up in bad prose. Works on technical subjects can at the same time be works of literary art, as the William Jameses, the Freuds, the Whiteheads, the Russells, and the Bronowskis of the world have proved. Of course technical communications addressed to specialists must employ technical language. But overloading it with jargon and employing a tortuous and cramped style is largely a matter of fashion, not of necessity.

Your objective should be to dress your ideas in a prose that will not only communicate them clearly, but also give people pleasure in the process of absorbing them. This, of course, is advice that every book on writing gives, and if it were easy to do, everyone would be doing it. It is not easy to do, but there is a technique that can help. What it primarily requires is that you consciously visualize the images you used in thinking up your ideas originally.

As must be obvious by now, I believe we do all our conceptual thinking in images rather than in words. It is more efficient to do so. An image can take a great mass of facts and synthesize them into a single abstract configuration. Given a person's inability to think about more than seven or eight items at one time, being able to compress the world in this way is a great convenience. Without it you would be limited to taking decisions on the basis of a few low-level facts.

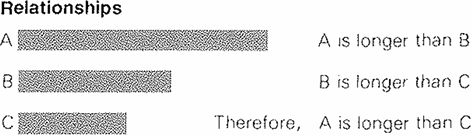

But bring together instead seven or eight of these abstract concepts, and you have in front of you an enormous amount of complex detail that you can easily manipulate mentally. Look, for example, at how much more quickly you can grasp the relationships of these three lines to each other from the image than you can from the words:

To compose clear sentences, then, you must begin by "seeing" what you are talking about. Once you have the image, you simply copy it into words. The reader, in turn, will re-create this image from your words, thereby not only grasping your thinking but also enjoying the exercise.

Let me demonstrate this process, first by showing how easily images appear when you are reading well-written prose, and then by giving you some hints on how to find the images lurking in bad prose so that you can rewrite it.