Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

THE TOP-DOWN APPROACH

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

22-3

2024-09-04

297

It is generally easier to start at the top and work down because you begin by thinking about the things that it is easiest for you to be sure of-your subject and the reader's knowledge of it, which you will remind him of in the introduction.

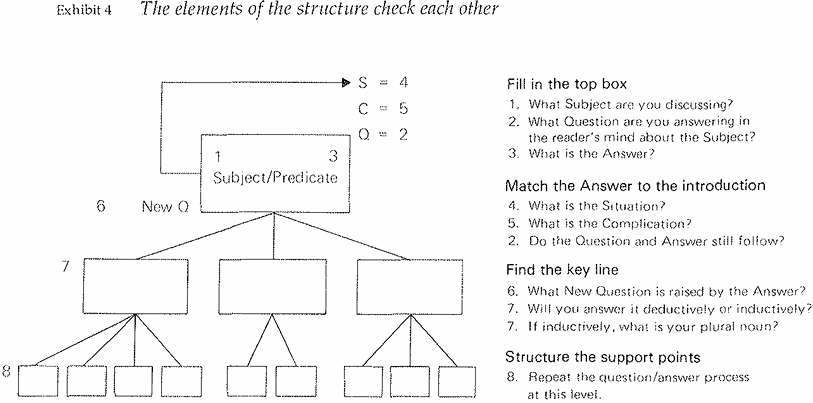

You don't want simply to sit down and begin writing the opening paragraph of the introduction, however. Instead, you want to use the structure of the introductory flow to pull the right points out of your head, one at a time. To do so, I suggest you follow the procedure shown in Exhibit 4 and described below.

I. Draw a box. This represents the box at the top of your pyramid. Write down in it the subject you are discussing, if you know it. If not, move on to step two.

2. Decide the Question. Visualize your reader. To whom are you writing, and what question do you want to have answered in his mind about the Subject when you have finished writing? State the Question, if you know it, or go on to step four.

3. Write down the Answer; if you know it, or note that you can answer it.

4. Identify the Situation. Next you want to prove that you have the clearest statement of the Question and the Answer that you can formulate at this stage. To do that, you take the Subject, move up to the Situation, and make the first noncontroversial statement about it you can make.

What is the first thing you can say about it to the reader that you know he will agree is true-either because he knows it, or because it is historically true and easily checked?

5. Develop the Complication. Now you begin your question/answer dialogue with the reader. Imagine that he nods his head in agreement and says, “Yes, I know that, so what?" This should lead you to think of what happened in that Situation to raise the reader's Question. Something went wrong, perhaps, some problem arose, or some logical discrepancy became apparent. What happened in the Situation to trigger the Question?

6. Recheck the Question and Answer: The statement of the Complication should immediately raise the Question you have already written down. If it does not, then change it to the one it does raise. Or perhaps you have the wrong Complication, or the wrong Question, and must think again.

The purpose of the entire exercise is to make sure you know what Question it is you are trying to answer. Once you have the Question, everything else falls into place relatively easily.

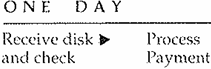

Let me demonstrate how your thinking would develop by using the technique to rewrite the memorandum shown in Exhibit 5, on the next page. It comes from the Accounting Department of a large soft drinks company in the United States.

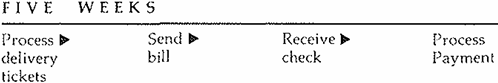

When the company's drivers deliver the product to a customer: they send back to the Accounting Department a delivery ticket with a set of code numbers, the date, and the amount of the delivery. These delivery tickets are the basis of the billing system, which works something like this:

One of the company's customers, a hamburger emporium we'll call Big Chief, gets an awful lot of deliveries. For its own accounting purposes, it would like to keep daily track of how the bill is mounting up. It wants to know if it can't keep the delivery tickets along with each delivery, record them on a computer disk, calculate the total, and then send the disk and its check once a month to the headquarters office of the beverage company. In other words, it is proposing a system that would work like this:

The head of the Accounting Department has been asked if the change would be feasible, and has answered in his present memorandum by saying essentially, "Here's

what we have found out about how the new system would work," without actually answering the question.

Had you been he and used the technique in Exhibit 4, here's what would have happened:

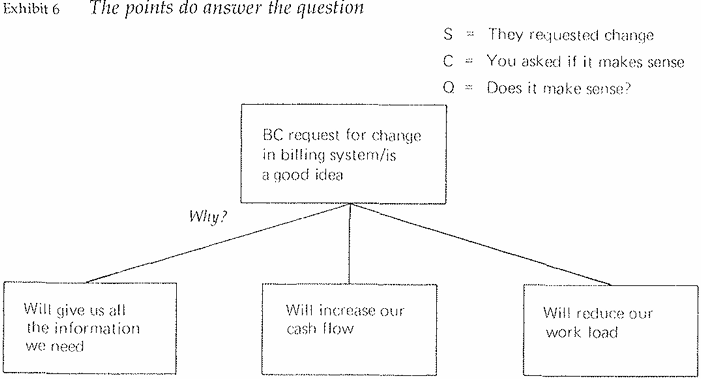

1. You would have drawn a box and said to yourself, "What Subject am I discussing?" (BC request for change)

2. What Question am I answering in the reader's mind about the Subject?" (Is it a good idea?)

3. What's the Answer? (Yes)

4. Now let me check that that is really the Question and really the Answer by thinking through the introduction. To do that I take the Subject and move up to the Situation. The first sentence of the Situation must be a statement about the Subject. What is the first noncontroversial thing I can think of to say about the Subject-something I know the reader will not question, but will accept as fact? (They have requested a change in the procedure.)

When you go to write the introduction out, you will of course in this paragraph explain the nature of the change, but for the purposes of working out your thinking you need only get clear the essence of the point of the paragraph.

5. Now you imagine the reader says, "Yes, I know that, so what?" This should lead you directly to a statement of the Complication. (You asked me whether it makes sense.)

The Question, as you've stated it, should now be the obvious next thing that would pop into the reader's mind (Does it make sense?). Since that's roughly what you've stated as your Question, you can see that both it and the Answer match, so you have checked that the point you are making is valid for the reader.

6. Given the statement that the change does make sense, you can now move down to determine what New Question would be raised in the reader's mind by your stating it to him. (Why?)

7. The answer to any Why? question is always "Reasons," so you know that the points you need across the Key Line must all be reasons. What might your reasons be?

It will give us the information we need.

It will increase our cash flow.

It will reduce our work load.

8. After determining that in fact these points are the right points and in logical order; the next step is to move down and spell out what you need to say to support each one. In the case of so short a document, however, you can probably proceed to write without further structuring. The supporting ideas are likely to be easily available in your mind and will come to you as you get to each section to write it.

As you can see, the technique forces a writer to draw from his mind only the information that will be relevant to his reader's question. But in doing so, it has helped push his thinking to deal fully with the question, rather than only partially as in the original example. And of course, if he follows the top-down order of presenting the ideas in writing, the entire message will be remarkably easy for the reader to absorb.