Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

THINKING FROM THE BOTTOM UP

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

8-1

2024-09-04

1233

THINKING FROM THE BOTTOM UP

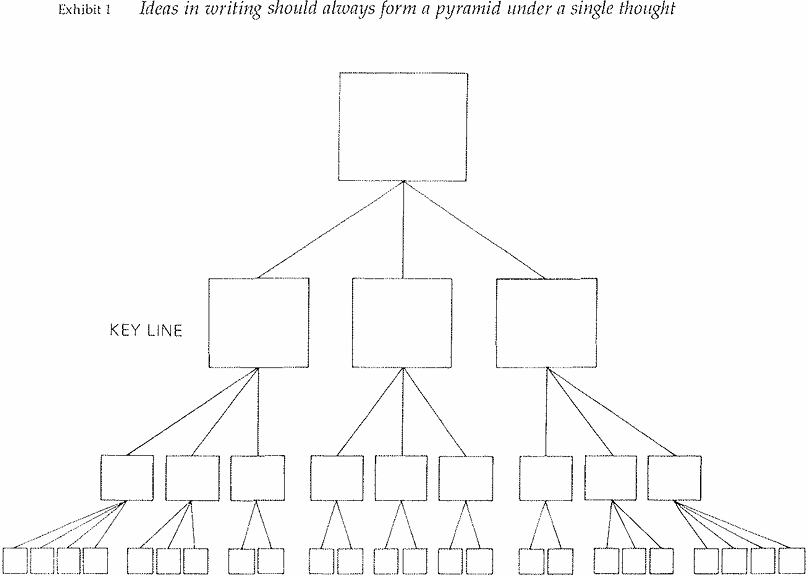

If you are going to group and summarize all your information and present it in a top-down manner, it would seem your document would have to look something like the structure opposite. The boxes stand for the individual ideas you want to present, with your thinking having begun at the lowest level by forming sentences that you grouped logically into paragraphs. You then grouped the paragraphs into sections, and the sections into the total memorandum represented by a single thought at the top.

If you think for a moment about what you actually do when you write, you can see that you develop your major ideas by thinking in this bottom-up manner. At the very lowest level in the pyramid, you group together sentences, each containing an individual idea, into paragraphs.

Let us suppose you bring together six sentences into one paragraph. The reason you bring together those six sentences and no others will clearly be that you see a logical relationship between them. And that logical relationship will always be that they are all needed to explain or defend the single idea of the paragraph, which is effectively a summary of them. You would not for example, bring together five sentences on finance and one on tennis, because their relevance to each other would be difficult to express in a single summary sentence.

Stating this summary sentence moves you up one level of abstraction and allows you to think of the paragraph as containing one point rather than six. With this act of efficiency you now group together, say, three paragraphs, each containing a single thought at a level of abstraction one step higher than that of the individual sentences.

The reason you from a section out of these three paragraphs, and no others, is also that you see a logical relationship between them. And the relationship is once again that they are all needed to explain or defend the single idea of the section, which again will be a summary of the three ideas in the paragraphs below them.

Exactly the same thinking holds true in bringing the sections together to form the document. You have three sections grouped together (each of which has been built up from groups of paragraphs, which in turn have been built up from groups of sentences) because they are all needed to support the single idea of the memorandum, which in turn is a summary of them.

Since you will continue grouping and summarizing until you have no more relationships to make, it is clear that every document you write will always be structured to support only one single thought-the one that summarizes your final set of groupings. This should be the major point you want to make, and all the ideas grouped underneath-provided you have built the structure properly-will serve to explain or defend that point in ever greater detail.

Fortunately, you can define in advance whether or not you have built the structure properly by checking to see whether your ideas relate to each other in a way that permits them to form pyramidal groups. Specifically they must obey three rules:

1. Ideas at any level in the pyramid must always be summaries of the ideas grouped below them.

2. Ideas in each grouping must always be the same kind of idea.

3. Ideas in each grouping must always be logically ordered.

Let me explain why these rules "must always" apply:

1. Ideas at any level in the pyramid must always be summaries of the ideas grouped below them. The first rule reflects the fact that the major activity you carry out in thinking and writing is that of abstracting to create a new idea out of the ideas grouped below. As we saw above, the point of a paragraph is a summary of its sentences, just as the point of a section is a summary of the points of its paragraphs, etc.

However, if you are going to be able to draw a point out of the grouped sentences or paragraphs, these groupings must have been properly formed in the first place. That's where rules 2 and 3 come in.

2. Ideas in each grouping must always be the same kind of idea. lf what you want to do is raise your thinking only one level of abstraction above a grouping of ideas, then the ideas in the grouping must be logically the same. For example, you can logically categorize apples and pears one level up as fruits; you can similarly think of tables and chairs as furniture. But what if you wanted to group together apples and chairs? You cannot do so at the very next level of abstraction, since that is already taken by fruit and furniture. Thus, you would have to move to a much higher level and call them "things" or "inanimate objects," either of which is far too broad to indicate the logic of the grouping.

In writing you want to state the idea directly implied by the logic of the grouping, which means that ideas in the grouping must all fall into the same logical category. Thus, if the first idea in a grouping is a reason for doing something, the other ideas in that grouping must also be reasons for doing the same thing. If the first idea is a step in a process, the rest of the ideas in the grouping must also be steps in the same process. If the first idea is a problem in the company, the others in the grouping must be related problems, and so on.

A shortcut in checking your groupings is to be sure that you can clearly label the ideas with a plural noun. Thus, you will find that all the ideas in the grouping will turn out to be things like recommendations, or reasons, or problems, or changes to be made. There is no limitation on the kinds of ideas that may be grouped, but the ideas in each grouping must be of the same kind, able to be described by one plural noun. How you make sure you get like kinds of ideas grouped together each time is explained more fully in Part Two.

3. Ideas in each grouping must always be logically ordered. That is, there must be a specific reason why the second idea comes second, and cannot come first or third. How you determine proper order is explained in detail in, Imposing Logical Order Essentially it says that there are only four possible logical ways in which to order a set of ideas:

- Deductively (major premise, minor premise, conclusion)

- Chronologically (first, second, third)

- Structurally (Boston, New York, Washington)

- Comparatively (first most important, second most important, etc.)

The order you choose reflects the analytical process you used to form the grouping. If it was formed by reasoning deductively the ideas go in argument order; if by working out cause-and-effect relationships, in time order; if by commenting on an existing structure, the order dictated by the structure; and if by categorizing, order of importance. Since these four activities- reasoning deductively, working out cause-and-effect relationships, dividing a whole into its parts, and categorizing are the only analytical activities the mind can perform, these are the only orders it can impose.

Essentially then, the key to clear writing is to slot your ideas into this pyramidal form and test them against the rules before you begin to write. If any of the rules is broken, it is an indication that there is a flaw in your thinking, or that the ideas have not been fully developed, or that they are not related in a way that will make their message instantly clear to the reader. You can then work on refining them until they do obey the rules, thus eliminating the need for vast amounts of rewriting later on.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)