Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Rethinking internal and external factors

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

281-13

2024-01-04

1308

Rethinking internal and external factors

The basic dichotomy between between internally and externally motivated change has long been recognized in historical linguistics but, as we shall see, it represents something of an idealization. Moreover it is often, in practice, difficult to disentangle internal and external factors involved. Even changes which appear historically to be internally motivated or ‘natural’ did not happen overnight: there must have been a period of variation, in which some people had adopted the change and others had not, and during which the ‘early adopters’ gradually passed on the change to the rest of the community, i.e. via contact, as in externally motivated change.

Much of our discussion of internally motivated change above assumed that certain kinds of change are more likely to occur or ‘natural’ than others because, either by reducing articulatory effort or making the system as a whole more economical, they make life easier for the speaker. But this apparently uncontroversial assumption in fact poses a number of problems. For example, if change tends to favor overall simplification from the speaker’s point of view, how and why did the language become ‘complex’ in the first place? Secondly, there is what William Labov has called the actuation problem: why does a change happen in a particular place at a particular time? Before addressing those questions, we should begin by noting that not all changes seem to go in the direction of simplification, as we have thus far presumed. Examples can be found of what have been termed ‘abnatural’ changes, which appear to promote additional complexity.

As we saw above, mergers often take place where phonemic oppositions have a low functional load. By this test, the southern English English  could-cud opposition looks like a prime candidate for merger: it affects very few word pairs, and since southerners have absolutely no difficulty understanding northerners, who do not have it, it seems like a luxury the southern English system could easily manage without. One might therefore surmise that the merger has happened in the north of England but not (yet?) in the south. In fact, historically, exactly the opposite is true: the north-south divide resulted not from merger in the north, but from a phonemic split in the south. Both southern and northern varieties had only

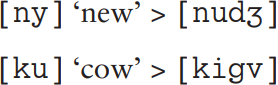

could-cud opposition looks like a prime candidate for merger: it affects very few word pairs, and since southerners have absolutely no difficulty understanding northerners, who do not have it, it seems like a luxury the southern English system could easily manage without. One might therefore surmise that the merger has happened in the north of England but not (yet?) in the south. In fact, historically, exactly the opposite is true: the north-south divide resulted not from merger in the north, but from a phonemic split in the south. Both southern and northern varieties had only  until the seventeenth century when, for reasons which remain unclear, what the phonetician John Wells has called the FOOT-STRUT split (after the two lexical sets affected) left the south, but not the north, with an additional phonemic opposition. Equally puzzling are some changes observed in Faroese, where some words have acquired additional consonants, requiring increased articulatory effort:

until the seventeenth century when, for reasons which remain unclear, what the phonetician John Wells has called the FOOT-STRUT split (after the two lexical sets affected) left the south, but not the north, with an additional phonemic opposition. Equally puzzling are some changes observed in Faroese, where some words have acquired additional consonants, requiring increased articulatory effort:

Neither of these developments is easy to square with what we have thus far assumed to be the natural direction of change. But might not the very notion of natural change, rather like that of ‘natural speech’, in fact be an impostor? There is some evidence that our perception of ‘natural’ is shaped by the kind of societies in which we live. Again, the example of Faroese is instructive here.

Faroese and Danish share a common ancestor in Old Norse, a north Germanic language spoken in Scandinavia and Viking settlements until about the thirteenth century. But the changes seen in the two languages in the intervening period have been very different in kind. Changes in Danish represent a radical simplification of Old Norse: its three genders have reduced to two; case-marking of nouns has been lost and the verbal paradigm has lost its personal inflections. Faroese, by contrast, retains much of the morphological complexity of Old Norse: the three-gender system and four-way case-marking system has remained, and the verb paradigm is still highly inflected. Compare the verb ‘to be’ in Old Norse, Faroese and Danish in the following table.

Although there has been some simplification of the Old Norse paradigm in Faroese (which no longer has distinct plural personal endings), changes in Danish have been far more radical, with the third person forms er and var extended to all persons. (To understand just how radical this change has been, try to imagine ‘to be’ in English as I is, you is, he/she is, we is, they is: some English speakers already extend was to plural persons in the past, notably football fans claiming ‘we was robbed!’). Why, then, has Danish undergone radical simplification, while Faroese has remained conservative with respect to Old Norse, and on occasions, as we saw above, even added to its complexity? The best explanation for the very different paths followed by Old Norse in Denmark and the Faroe Islands lies in the contrasting social network structures to be found in the two settings.

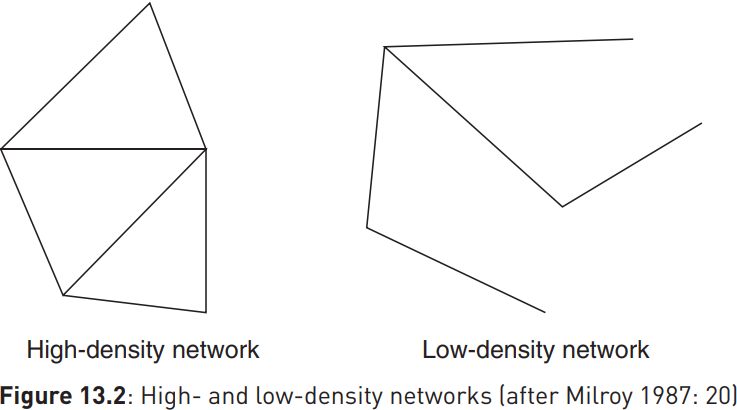

The concept of social network, first employed in sociolinguistics by Lesley Milroy in her 1980 Belfast study, was used to describe the nature of the bonds, or ties, between members of a community. In close-knit communities, network ties are invariably dense (many people know many others within the community) and multiplex (people know each other in more than one context, e.g. as kinsman, co-worker, member of the same church or sports team); by contrast, in loose-knit communities, networks are of lower density, with fewer people knowing many others within the community, and then perhaps interacting with them only in one context, as illustrated in Figure 13.2, in which each node represents an individual and the lines his/her ties to others in the community:

Networks and rate of change

Externally motivated change is generally slow in communities where social networks are dense and multiplex, particularly in isolated areas where there are few weak ties to other networks. Conversely, in communities characterized by low-density social networks, change is more rapid because there are large numbers of weak ties between networks, which facilitate the transmission of new variants.

Dense and multiplex networks have strong internal ties, but few external ones: they are typically found in relatively isolated areas. Low-density networks, by contrast, have high numbers of weak ties, i.e. casual links between its members and those of other networks. Investment in these weak ties by either side is often minimal, but they are important nonetheless in providing the bridges between networks across which change can be transmitted. Low-density networks typify high-contact areas, notably major cities or areas of high population density where communications and transport infrastructure are good.

The relative conservatism of Faroese is best understood in terms of the isolation and village-based social structure of the Faroe Islands. With a population of around 50,000 people living on small, remote islands situated nearly 1,000 km from the kingdom of Denmark of which they form part, the Faroe Islands consist largely of close-knit communities with relatively few weak ties bringing in changes from outside. Changes are few in number, but where they do occur, they may preserve or even increase linguistic complexity because dense, multiplex social networks with few outsiders are better placed to support it than those with an abundance of weak ties to members of other networks, with whom unfamiliar forms have be negotiated.

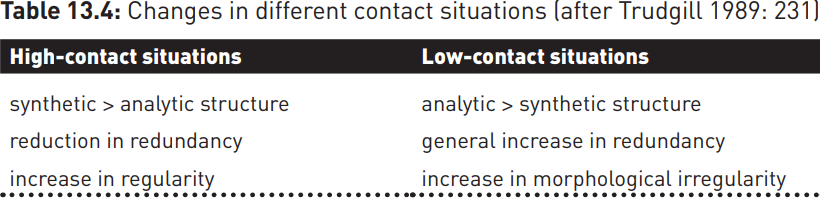

By contrast, Denmark, a small and relatively densely populated country situated on the European mainland at a crossroads between Germany, with which it shares a land border, and the Scandinavian countries, with which it shares close economic and cultural ties, is far from isolated. Consequently, the changes witnessed in mainland Danish have tended to be of the simplifying kind associated with high-contact areas – for example, a gradual shift from a synthetic (highly inflected) structure to an analytical one (in which grammatical relations are more usually marked by free morphemes, e.g. prepositions). Trudgill has suggested a typology of changes associated with high- and low-contact situations, which can be seen in the following table.

Contact and isolation offer an alternative explanation for Labov’s observation that it is often the intermediate rather than upper social classes which lead change. Instead of interpreting this finding in ideological terms, i.e. in terms of the social insecurity or aspirations of these groups, it may simply be the case that these groups have greatest contact with members of other social groups, and therefore are most likely to adopt changes and pass them on.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)