Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Expletive it subjects

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

291-8

28-1-2023

2481

Expletive it subjects

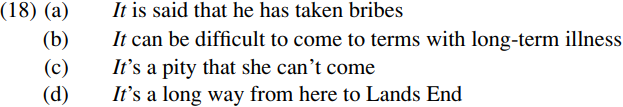

So far, all the constructions we have looked at have involved a finite T agreeing with a noun or pronoun expression which carries interpretable person/number  -features. However, English has two expletive pronouns which (by virtue of being non-referential) carry no interpretable

-features. However, English has two expletive pronouns which (by virtue of being non-referential) carry no interpretable  -features. One of these is expletive it in sentences such as:

-features. One of these is expletive it in sentences such as:

The pronoun it in sentences like these appears to be an expletive, since it cannot be replaced by a referential pronoun like this or that, and cannot be questioned by what. Let’s examine the syntax of expletive it by looking at the derivation of a sentence like (18a).

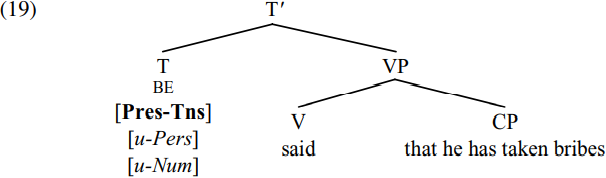

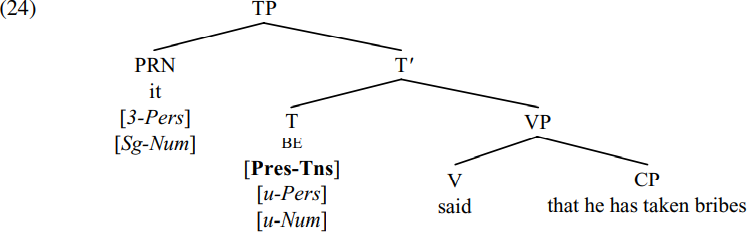

Suppose that we have reached the stage of derivation where the (passive participle) verb said has been merged with its CP complement that he has taken bribes to form the VP said that he has taken bribes. Merging this VP with the tense auxiliary BE forms the structure shown in simplified form below:

In accordance with Pesetsky’s Earliness Principle, we might expect T-agreement to apply at this point. Accordingly, the probe BE (which is active by virtue of its uninterpretable person/number  -features) searches for an active goal to value its unvalued

-features) searches for an active goal to value its unvalued  -features. It might at first sight seem as if the CP headed by that is an appropriate goal, and is a third-person-singular expression which can value the person/number features of BE. However, it seems unlikely that such clauses have person/number features. One reason for thinking this is that even if the that-clause in (19) is coordinated with another that-clause as in (20) below, the verb BE remains in the singular form is:

-features. It might at first sight seem as if the CP headed by that is an appropriate goal, and is a third-person-singular expression which can value the person/number features of BE. However, it seems unlikely that such clauses have person/number features. One reason for thinking this is that even if the that-clause in (19) is coordinated with another that-clause as in (20) below, the verb BE remains in the singular form is:

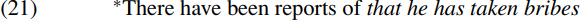

If each of the italicized clauses in (20) were singular in number, we would expect the bracketed coordinate clause to be plural (in the same way as the coordinate structure John and Mary is a plural expression in a sentence like John and Mary are an item): but the fact that the passive auxiliary is remains singular in (20) suggests that the CP has no number properties of its own. Nor indeed does the that-clause in (19) have an unvalued case feature which could make it into an active goal, since that-clauses appear to be caseless (as argued by Safir 1986), in that a that-clause cannot be used in a position like that italicized in (21) below where it would be assigned accusative case by a transitive preposition such as of:

If the CP in (19) has no uninterpretable case feature, it is inactive and so cannot value the  -features of BE.

-features of BE.

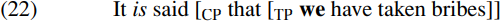

However, a question we might ask about (19) is whether BE could instead agree with the subject of the that-clause, namely he: after all, he has an uninterpretable case feature (making it active), and is a third-person-singular expression and so could seemingly value the unvalued person/number features of BE. Yet it is clear that BE does not in fact agree with HE, since if we replace HE by the first-personplural subject we, BE still surfaces in the third-person-singular form is – as (22) below illustrates:

Something, then, must prevent be from agreeing with we – but what? The answer lies in a constraint developed by Chomsky termed the Phase Impenetrability Condition/PIC. Since understanding PIC requires a prior understanding of the notion of phase developed by Chomsky in recent work (1998, 1999, 2001), let’s first take a look at what phases are.

We suggested that a fundamental principle of UG is a Locality Principle which requires all grammatical operations to be local. Using the probe–goal terminology, we can construe this as meaning that all grammatical operations involve a relation between a probe P and a local goal G which is sufficiently ‘close’ to the probe. However, an important question to ask is why probe–goal relations must be local. In this connection, Chomsky (2001,p. 13) remarks that ‘the P, G relation must be local’ in order ‘to minimize search’ (i.e. in order to ensure that a minimal amount of searching will enable a probe to find an appropriate goal). His claim that locality is forced by the need ‘to minimize search’ suggests a processing explanation: the implication is that the Language Faculty can only process limited amounts of structure at one time – and, more specifically, can only hold a limited amount of structure in its ‘active memory’ (Chomsky 1999, p. 9). In order to ensure a ‘reduction of computational burden’ (1999, p. 9) Chomsky proposes that ‘the derivation of EXP [ressions] proceeds by phase’ (ibid.), so that syntactic structures are built up one phase at a time. He maintains (2001, p. 14) that ‘phases should be as small as possible, to minimize memory’. More specifically, he suggests (1999, p. 9) that phases are ‘propositional’ in nature, and hence include CPs. His rationale for taking CP to be phases is that CP represents a complete clausal complex (including a specification of force).

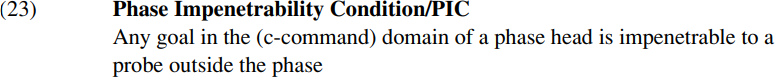

In what sense do phases ensure that grammatical operations are purely local? The answer given by Chomsky is that any goal within the (c-command) domain of the phase (i.e. any goal c-commanded by the head of the phase) is impenetrable to further syntactic operations. He refers to this condition as the Phase Impenetrability Condition/PIC – and we can state it as follows (cf. Chomsky 2001, p. 5, ex. 6):

Stated in a form like (23), the relevant condition clearly begs the question of why a goal positioned ‘below’ a phase head should be impenetrable to a probe positioned ‘above’ the phase. Chomsky’s answer (2001, p. 5) is that once a complete phase has been formed, the domain of the phase head (i.e. its complement) undergoes a transfer operation by which it is simultaneously sent to the phonological component to be assigned an appropriate phonetic representation, and to the semantic component to be assigned an appropriate semantic representation – and hence no constituent in the relevant domain is thereafter able to undergo any further syntactic operations. So, for example, once the operations which take place on the CP cycle have been completed, the TP which is the domain/complement of the phase head C will be sent to the phonological and semantic components for processing. As a result, TP is no longer accessible in the syntax, and hence neither TP itself nor any constituent of TP can subsequently serve as a goal for a higher probe of any kind in the syntax.

In the light of the Phase Impenetrability Condition (23), let’s return to our earlier structure (19) and ask why the auxiliary is in the main clause can’t agree with the subject he of the complement clause. The answer is as follows. The complement clause that he has taken bribes is a CP, hence a phase. The domain of that CP (i.e. the constituent which is the complement of the head C of CP) is the TP he has taken bribes.

This means that neither this TP nor any of its constituents can serve as a goal for a probe outside CP. Since is in (19) lies outside the bracketed CP phase, and he lies inside its bracketed TP domain, PIC prevents agreement between the two. (See Polinsky and Potsdam 2001, and Branigan and MacKenzie 2002 for an analysis of apparent long-distance agreement in terms of PIC.)

So far, what we have established in relation to the structure in (19) is that be cannot agree with the that-clause because the latter is inactive and has no  -features or case feature; nor can BE agree with he, because PIC makes he impenetrable to BE. It is precisely because BE cannot agree with CP or with any of its constituents that expletive it has to be used, in order to satisfy the [EPP] requirement of T, and to value the

-features or case feature; nor can BE agree with he, because PIC makes he impenetrable to BE. It is precisely because BE cannot agree with CP or with any of its constituents that expletive it has to be used, in order to satisfy the [EPP] requirement of T, and to value the  -features of T. In keeping with the Minimalist spirit of positing only the minimal apparatus which is conceptually necessary, let’s further suppose that expletive it has ‘a full complement of

-features of T. In keeping with the Minimalist spirit of positing only the minimal apparatus which is conceptually necessary, let’s further suppose that expletive it has ‘a full complement of  -features’ (Chomsky 1998, p. 44) but that (as Martin Atkinson (pc) suggests) these are the only features carried by it in its expletive use. More specifically, let’s assume that expletive it carries the features [third-person, singular-number]. Since expletive it is a ‘meaningless’ expletive pronoun, these features will be uninterpretable. Given this assumption, merging it as the specifier of the T-bar in (19) above will derive the structure (24) below (with interpretable features shown in bold, and uninterpretable features in italics):

-features’ (Chomsky 1998, p. 44) but that (as Martin Atkinson (pc) suggests) these are the only features carried by it in its expletive use. More specifically, let’s assume that expletive it carries the features [third-person, singular-number]. Since expletive it is a ‘meaningless’ expletive pronoun, these features will be uninterpretable. Given this assumption, merging it as the specifier of the T-bar in (19) above will derive the structure (24) below (with interpretable features shown in bold, and uninterpretable features in italics):

At this stage in the derivation, the pronoun it can serve as a probe because it is the highest head in the structure, and because it is active by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features. Likewise, the auxiliary BE can serve as a goal for it because BE is c-commanded by it and BE is active by virtue of its uninterpretable

-features. Likewise, the auxiliary BE can serve as a goal for it because BE is c-commanded by it and BE is active by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features. Feature-Copying (7) can therefore apply to value the unvalued

-features. Feature-Copying (7) can therefore apply to value the unvalued  -features on BE as third person singular (via agreement with it), and Feature-Deletion (14) can apply to delete the uninterpretable

-features on BE as third person singular (via agreement with it), and Feature-Deletion (14) can apply to delete the uninterpretable  -features of both it and BE, so deriving:

-features of both it and BE, so deriving:

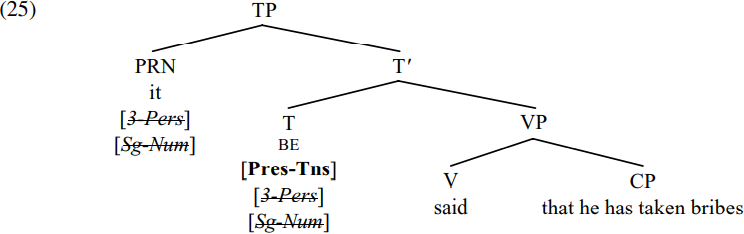

As required, all unvalued features have been valued at this point (BE ultimately being spelled out in the PF component as is), and all uninterpretable features deleted. The resulting structure (25) is subsequently merged with a null declarative complementizer. The deleted uninterpretable person/number features of it and BE will be visible in the PF component and the syntax, but not in the semantic component; the undeleted [Pres-Tns] feature of be will be visible in all three components. Hence, BE will be spelled out as is in the PF component, since the phonology can ‘see’ the third-person, singular-number, present-tense features carried by BE.

There are two particular features of the analysis outlined above which merit further comment. One is that we have assumed that expletive it carries person and number features, but no gender feature and no case feature. While it clearly carries an interpretable (neuter/inanimate) gender feature when used as a referential pronoun (e.g. in a sentence like This book has interesting exercises in it, where it refers back to this book), it has no semantic interpretation in its use as an expletive pronoun, and so can be assumed to carry no interpretable gender feature in such a use. The reason for positing that expletive it is a caseless pronoun is that it is already active by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features, and hence does not ‘need’ a case feature to make it active for agreement (unlike subjects with interpretable

-features, and hence does not ‘need’ a case feature to make it active for agreement (unlike subjects with interpretable  -features). Some suggestive evidence that expletive it may be a caseless pronoun comes from the fact that it has no genitive form its – at least for speakers like me who don’t say (e.g.) ∗He was annoyed at its raining.

-features). Some suggestive evidence that expletive it may be a caseless pronoun comes from the fact that it has no genitive form its – at least for speakers like me who don’t say (e.g.) ∗He was annoyed at its raining.

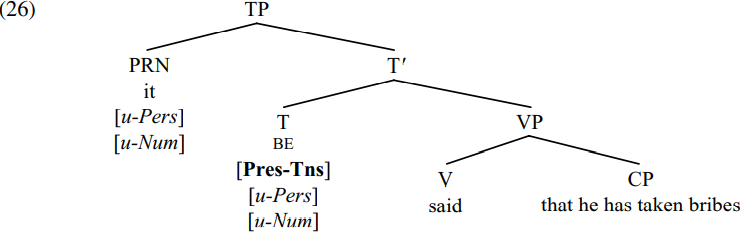

A further assumption worth commenting on is that we have assumed that expletive it is intrinsically third person singular, and that this is why BE ends up in the third-person-singular form is in sentences like (18a) It is said that he has taken bribes. However, if we were to accept Chomsky’s view that all uninterpretable features enter the derivation unvalued, we’d have to say that the pronoun it enters the derivation with unvalued person/number features, as in (26) below:

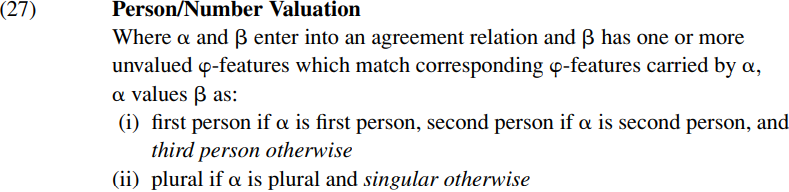

The obvious question which such an analysis would raise is how a pronoun with unvalued person/number features can value the unvalued person/number features of T (and conversely). To answer this question, we’d have to invoke default number/person valuation conditions such as those italicized below:

(27i) would ensure that the person features of both it and BE are assigned the default (otherwise) value [3-Pers]; and (27ii) would ensure that the number features of both it and BE are assigned the default value [Sg-Num]. We will not attempt to choose between the analyses in (24) and (26) here, but for concreteness we will henceforth assume (24).

Let’s now turn to consider the question of how we handle sentences like the following, which contain so-called weather it:

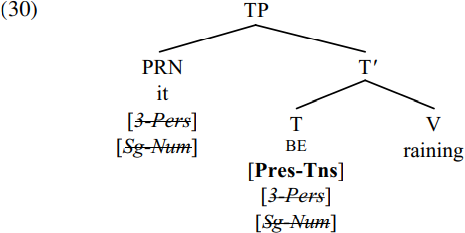

One way of analyzing a sentence like (28a) is to treat RAIN as a predicate which has no  -marked argument, and to take it to be a non-referential (expletive) pronoun. This would mean that the first stage in the derivation of (28a) is for the tense auxiliary BE to be merged with the verb RAIN (which is ultimately spelled out as the form raining because the progressive auxiliary BE requires a complement headed by a verb in the ing-form). Merging expletive it as the specifier of the resulting T-bar BE raining would derive the structure (29) below, if we assume (for expository purposes) that it is intrinsically third person singular:

-marked argument, and to take it to be a non-referential (expletive) pronoun. This would mean that the first stage in the derivation of (28a) is for the tense auxiliary BE to be merged with the verb RAIN (which is ultimately spelled out as the form raining because the progressive auxiliary BE requires a complement headed by a verb in the ing-form). Merging expletive it as the specifier of the resulting T-bar BE raining would derive the structure (29) below, if we assume (for expository purposes) that it is intrinsically third person singular:

At this point, it is the highest head in the overall structure, and is active (by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features) and so can serve as a probe. [T BE] is c-commanded by it and is also active (by virtue of its own uninterpretable

-features) and so can serve as a probe. [T BE] is c-commanded by it and is also active (by virtue of its own uninterpretable  - features), and so can serve as a goal for the probe it. Accordingly, the unvalued person/number features on BE are valued via the Feature-Copying operation (7), with the result that the

- features), and so can serve as a goal for the probe it. Accordingly, the unvalued person/number features on BE are valued via the Feature-Copying operation (7), with the result that the  -features of BE are assigned the same values as those of it. Since both it and BE are

-features of BE are assigned the same values as those of it. Since both it and BE are  -complete (by virtue of carrying both person and number features), and since their

-complete (by virtue of carrying both person and number features), and since their  -features have matching values, each can delete the uninterpretable

-features have matching values, each can delete the uninterpretable  -features of the other in accordance with Feature-Deletion (14), so deriving:

-features of the other in accordance with Feature-Deletion (14), so deriving:

The deleted uninterpretable person/number features of it and BE will be visible in the PF component and the syntax, but not in the semantic component; the undeleted [Pres-Tns] feature of BE will be visible in all three components. Hence, BE will be spelled out as IS in the PF component, since PF can ‘see’ the third-person, singular-number, present-tense features carried by BE. The resulting TP will subsequently be merged with a null declarative-force complementizer.

A key assumption in the analysis outlined above is that expletive it is a meaningless ‘filler’, and so non-referential. However, this assumption would seem to be called into question by the observation that expletive it can serve as the antecedent of PRO: cf.

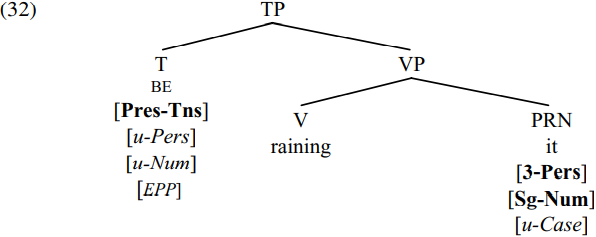

If we suppose that only a referential pronoun can serve as the controller of PRO, a plausible conclusion to draw is that expletive it is referential (in a sense made precise by Chomsky 1981, who suggests that expletive it is a quasi-argument). And if weather it in sentences like (28a,b) is referential, it is also plausible to suppose that it is initially merged as a (quasi-)argument of the weather predicate with which it is associated. If we suppose that weather verbs like rain/snow are unaccusative (as is suggested by the fact that in Italian they can be used with the auxiliary essere ‘be’ in perfect-participle forms), this would mean that it in (28a,b) originates as the complement of the verb rain/snow. If weather it is indeed referential and if this means that its person/number features are interpretable, then it follows that weather it will also need an unvalued case feature to make it active in the syntax. Assuming all of this, we will have the structure shown in simplified form in (32) below at the stage when T is merged with its complement:

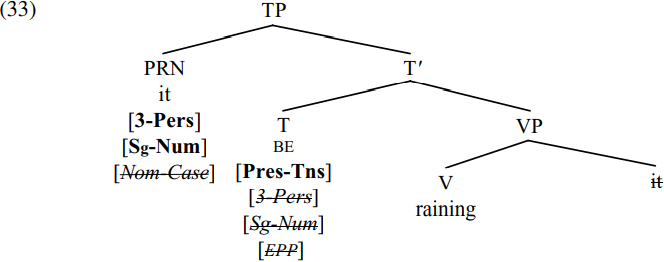

The unvalued person/number features of BE will be valued as third person singular in accordance with Feature-Copying (7), and deleted in accordance with Feature-Deletion (14). The unvalued case feature on it will be valued as nominative by Nominative Case Assignment (9), and deleted by Feature-Deletion (14). The [EPP] feature of T will simultaneously trigger movement of it (which is active by virtue of its unvalued case feature) to spec-TP, so deriving the structure in (33) below (simplified by not showing features carried by the trace copy of it):

As required, all uninterpretable features have been deleted, so the resulting derivation is convergent. If the analysis of expletive it outlined here is along the right lines it suggests that (contrary to what we assumed earlier) expletive it is not a pure ‘dummy’ element inserted in spec-TP to satisfy the [EPP] requirement of T, but rather is a (quasi-)argument which originates internally within VP. Of course, if expletive it carries case, we have to ask why (as noted above) it has no genitive form: however, this is arguably just a lexical idiosyncrasy, since even in its referential use it has no strong genitive form (Peter Evans (pc) points out), as we see from the ungrammaticality of? ∗Its watering the flowers is something I don’t like about my cat.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)