Comparing raising and control predicates

It might at first sight seem tempting to conclude from our discussion of long-distance passivisation structures like (74) and raising structures like (80) that all clauses containing a structure of the form verb+ to+ infinitive have a similar derivation to that in (74) and (80) in which some expression is raised out of the infinitive complement to become the subject of the main clause. However, any such conclusion would be undermined by our claim that some verbs which take to+ infinitive complements are control predicates. In this connection, consider the difference between the two types of infinitive structure illustrated below:

As used in (81), the verb seem is a raising predicate, but the verb want is a control predicate. We will see that this reflects the fact that the verbs seem and want differ in respect of their argument structure. We can illustrate this by sketching out the derivation of the two sentences.

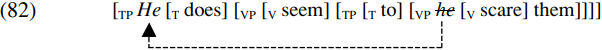

In the raising structure (81a), the verb scare merges with (and assigns the EXERIENCER θ-role to) its internal argument/thematic complement them. The resulting V-bar scare them then merges with (and assigns the AGENT θ-role to) its external argument/thematic subject he. The resulting VP he scare them is then merged with the infinitival tense particle to, so forming the TP to he scare them. This in turn merges with the raising verb seem to form the VP seem to he scare them. The resulting VP seem to he scare them is subsequently merged with the (emphatic) auxiliary does. The [EPP] feature carried by [T does] requiring it to have a structural subject triggers raising of the closest nominal c-commanded by does (namely he) from being thematic subject of scare them to becoming structural subject of does – as shown in schematic form below:

The resulting TP is then merged with a null complementizer marking the sentence as declarative in force.

A key assumption made in the raising analysis in (82) is that the verb seem (as used there) is a one-place predicate whose only argument is its infinitival TP complement, to which it assigns an appropriate θ-role – perhaps that of THEME argument of seem. This means that the VP headed by seem has no thematic subject: note, in particular, that the verb seem does not θ-mark the pronoun he, since he is θ-marked by scare, and the θ -CRITERION (30) rules out the possibility of any argument being θ-marked by more than one predicate. Nor does the VP headed by seem have a structural subject at any stage of derivation, since he raises to become the subject of the TP containing does, not of the VP containing seem.

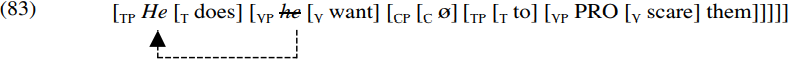

Now let’s turn to consider the derivation of the control infinitive structure (81b) He does want to scare them. As before, the verb scare merges with (and assigns the EXPERIENCER θ-role to) its internal argument (i.e. thematic complement)them. The resulting V-bar scare them then merges with (and assigns the AGENT θ-role to) its external argument. Given the assumption we made that control infinitives have a particular kind of null pronominal subject known as ‘big PRO’, the thematic subject of scare them will be PRO, and this will be merged in spec-VP (in accordance with the VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis), and thereby be assigned the θ-role of AGENT argument of scare. The resulting VP PRO scare them then merges with infinitival to, forming the TP to pro scare them. Given the conclusion we drew that control infinitives are CPs, this TP will in turn merge with a null infinitival complementiser to form the CP ø to PRO scare them. The CP thereby formed serves as the internal argument (and thematic complement) of the verb want, so is merged with want and thereby assigned the θ-role of THEME argument of want. The resulting V-bar want ø to PRO scare them then merges with its external argument (and thematic subject) he, assigning he the thematic role of EXPERIENCER argument of want. The resulting VP he want ø to PRO scare them is then merged with the tense auxiliary DO, forming the T-bar does he want ø to PRO scare them. The [EPP] feature carried by [T does] requires it to have a structural subject, and this requirement is satisfied by moving the closest noun or pronoun expression c-commanded by does (namely the pronoun he) to become the structural subject of does, as shown in simplified form below:

The TP in (83) is then merged with a null complementizer marking the sentence as declarative in force. The resulting structure satisfies the θ-criterion (which requires each argument to be assigned a single θ-role, and each θ-role to be

assigned to a single argument), in that he is the EXPERIENCER argument of want, the bracketed CP in (83) is the THEME complement of want, PRO is the AGENT argument of scare, and them the EXPERIENCER argument of scare.

The analysis of control assumes that the PRO subject of a control infinitive like that bracketed in (81b) He does want to scare them is merged in spec-VP, and not in spec-TP. As we have seen, the requirement for PRO to be generated in spec-VP follows from the Predicate-Internal Argument Hypothesis (19) which posits that arguments are generated internally to a projection of their predicate, so that PRO (by virtue of being the thematic subject of scare) is generated as the specifier of the VP headed by scare. Baltin (1995, p. 244) provides an empirical argument in favor of claiming that the PRO subject is positioned in spec-VP in control infinitives. He notes that under the spec-VP analysis in (83), PRO will be positioned between to and scare rather than between want and to (as would be the case if PRO were in spec-TP), and hence PRO will not block to from criticizing onto want forming wanta/wanna. The fact that the contraction is indeed possible – as we see from (84) below:

leads Baltin to conclude that PRO is merged in spec-VP, and remains there throughout the derivation – at no point becoming the subject of infinitival to. Of course, an ancillary assumption which has to be made is that the null C which intervenes between want and to in (83) does not block contraction. One way of accounting for this might be to assume that to first criticizes onto the null C constituent introducing the complement clause in (83), and then subsequently (together with the null complementizer to which it has attached) criticizes onto the verb want.

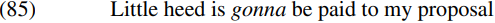

An important conclusion which Baltin draws from his analysis of wanna contraction is that infinitival to in control structures does not have an [EPP] feature, and hence does not have a specifier at any stage of derivation. In much the same way, we can argue that the possibility of gonna contraction in raising structures such as (85) below:

provides evidence in support of positing that infinitival to in raising structures does not have an [EPP] feature either. Prior to passivisation, (85) will have the structure shown informally in (86) below:

If the idiomatic nominal little heed is raised directly to become the subject of is without first becoming the subject of to, (85) will have the structure shown in (87) below after passivisation has applied:

The absence of any constituent intervening between to and going means that to can criticize onto going, forming gonna. But if to in raising/passive infinitive structures has an [EPP] feature, the idiomatic nominal little heed will have to raise to become the specifier of infinitival to before becoming the subject of is, so that after passivisation we will have the structure (88) below:

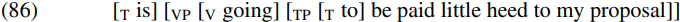

We would then expect that the presence of a trace copy of little heed intervening between going and to should block contraction, and we would therefore wrongly predict that gonna contraction is not possible, and hence that (85) is ungrammatical. The fact that contraction is indeed possible suggests that infinitival to does not have an [EPP] feature in passive infinitive structures. Moreover, Boˇskovi´c (2002b) argues that the ungrammaticality of double there structures like:

We would then expect that the presence of a trace copy of little heed intervening between going and to should block contraction, and we would therefore wrongly predict that gonna contraction is not possible, and hence that (85) is ungrammatical. The fact that contraction is indeed possible suggests that infinitival to does not have an [EPP] feature in passive infinitive structures. Moreover, Boˇskovi´c (2002b) argues that the ungrammaticality of double there structures like:

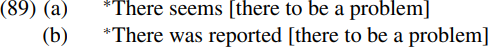

provides further evidence that infinitival to in raising/passive structures does not have an [EPP] feature, since if it did we should expect the bracketed infinitive complements to allow an expletive subject of their own. Epstein and Seeley (1999) likewise argue that A-movement always takes place in a single step, and not in multiple (successive-cyclic) steps. Given Baltin’s argument that to does not have an [EPP] feature in control infinitives either, the more general conclusion which these two sets of claims invite is that:

And indeed this assumption is implicit in the analyses outlined in (79), (80), (82), (83) and (87) above.

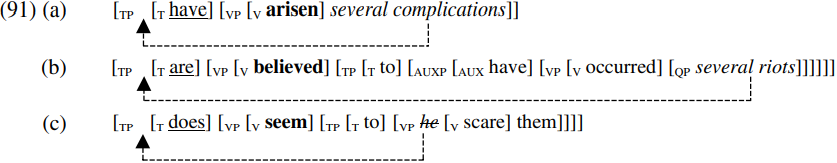

There are interesting parallels between the derivation of unaccusative structures like (91a) below (sketched in (48) above), passive structures like (91b) (sketched in (70) above) and raising structures like (91c) (sketched in (82) above):

In each of these structures, a (bold-printed) one-place predicate which has no external argument (and which therefore projects into an intransitive VP which has a complement but no subject) allows movement of the closest (italicized) constituent c-commanded by the underlined T constituent out of the containing VP into spec-TP. For instance, the VP headed by the unaccusative verb arisen in (91a)

has no subject and consequently allows its complement several complications to move out of its containing VP into spec-TP. Likewise, the VPs headed by the passive verb believed and the unaccusative verb occurred in (91b) have no subject of their own, and so allow several riots to move out of both VPs into spec-TP in the main clause. Similarly, the VP headed by the raising verb seem in (91c) has no subject of its own and so allows the pronoun he to move into the main-clause spec-TP position.

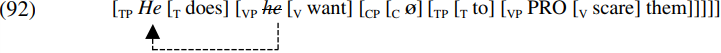

What all of this points to is that an intransitive (subjectless) VP allows a nominal c-commanded by its head verb to be attracted by a higher T constituent to move into spec-TP. However where a VP has a thematic subject of its own, it is this subject which raises to spec-TP (because the Attract Closest Principle requires T to attract the closest nominal which it c-commands to raise to spec-TP). So, for example, in (91c) above, it is the subject he of the VP headed by scare which raises to spec-TP and thereby becomes the subject of the present-tense auxiliary does. The same is true of a control structure like (92) below (repeated from (83) above):

Here, the pronoun he originates as the thematic subject of want, and hence raises to spec-TP by virtue of being the closest nominal c-commanded by [T does].

What this suggests is that the particular property of passive, unaccusative and raising predicates which enables them to permit A-movement of a nominal argument which they c-command is that they are intransitive and therefore do not project an external argument (so that the VP they head is subjectless). By contrast, verbs which project an external argument of their own (and hence occur in a VP which has a thematic subject) require this subject to be attracted by a higher T constituent to move into spec-TP. These distinct patterns of movement are a consequence of the Attract Closest Principle. (See Culicover and Jackendoff 2001 for arguments that control and raising predicates have a distinct syntax.)

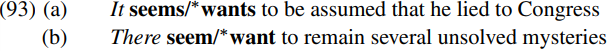

Having looked at the syntax of control predicates on the one hand and raising predicates on the other, we end by looking briefly at the question of how we can determine whether a given predicate which selects an infinitival to complement is a control predicate or a raising predicate. In this connection, it should be noted that there are a number of syntactic differences between raising and control predicates which are a direct reflection of the different thematic properties of these two types of predicate. For example, raising predicates like seem can have expletive it/there subjects, whereas control predicates like want cannot:

(The expletive nature of it in (93a) is shown by the fact that it cannot be substituted by a referential pronoun like this/that, or questioned by what? Likewise, the expletive nature of there in (93b) is shown by the fact that it cannot be substituted by a referential locative adverb like here, or questioned by where?) This is because control predicates like want are two-place predicates which project a thematic subject (an EXPERIENCER in the case of want, so that the subject of want must be an expression denoting an entity capable of experiencing desires), and non-referential expressions like expletive it/there are clearly not thematic subjects and so cannot be assigned a θ-role. By contrast, raising predicates like seem have no thematic subject, and hence impose no restrictions on the choice of structural subject in their clause, so allowing a (non-thematic) expletive subject.

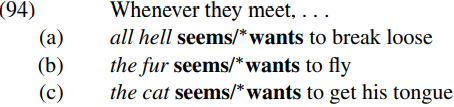

Similarly, raising predicates like seem (but not control predicates like want) allow idiomatic subjects such as those italicized below:

The ungrammaticality of sentences like ∗All hell wants to break loose can be attributed to the fact that want is a control predicate, and hence (in order to derive such a structure) it would be necessary to assume that all hell originates as the subject of want, and that break loose has a separate PRO subject of its own: but this would violate the requirement that (on its idiomatic use) all hell can only occur as the subject of break loose, and conversely break loose (in its idiomatic use) only allows all hell as its subject. By contrast, All hell seems to break loose is grammatical because seem is a raising predicate, and so all hell can originate as the subject of break loose and then be raised up to become the subject of the null tense constituent [T ø] in the seem clause. The null T agrees in person and number with the 3Sg expression all hell, but because there is no overt auxiliary in the head T position of TP to spell out the relevant features, the tense and agreement features of T are spelled out on the verb seem (via the morphological operation of Affix Hopping), with the consequence that the main verb ultimately surfaces in the third-person-singular present-tense form seems.

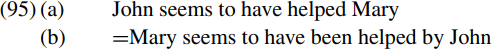

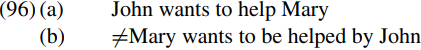

A further property which differentiates the two types of predicate is that raising predicates like seem preserve truth-functional equivalence under passivisation, so that (95a) below is cognitively synonymous with (95b):

By contrast, control predicates like want do not preserve truth-functional equivalence under passivisation, as we see from the fact that (96a) below is not cognitively synonymous with (96b):

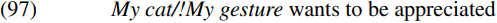

Moreover, there are pragmatic restrictions on the choice of subject which control predicates like want allow (in that the subject generally has to be a rational being, not an inanimate entity) – as we see from (97) below (where ! marks pragmatic anomaly):

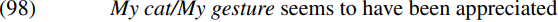

By contrast, raising predicates freely allow animate or inanimate subjects:

The different properties of the two types of predicate stem from the fact that control predicates like want θ-mark their subjects, whereas raising predicates like seem do not: so, since want selects an experiencer subject as its external argument (and prototypical EXPERIENCERS are animate beings), want allows an animate subject like my cat, but not an inanimate subject like my gesture. By contrast, since raising predicates like seem do not θ-mark their subjects, they allow a free choice of subject.

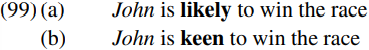

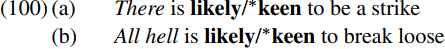

A final remark to be made is that although our discussion of raising and control predicates has revolved around verbs, a parallel distinction is found in adjectives. For example, in sentences such as:

the adjective likely is a raising predicate and keen a control predicate. We can see this from the fact that likely allows expletive and idiomatic subjects, but keen does not:

This is one reason why we have talked about different types of predicate (e.g. drawing a distinction between raising and control predicates) rather than different types of verb.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة